Serving the Score

“Serving the Score” by Ryan Touhy, Music Director for The Secret Garden

“Anything you do, let it come from you. Then it will be new. Give us more to see”

– Stephen Sondheim, Sunday in the Park with George

Ryan Touhy, Credit: Niki Cousineau. Passion, 2015

The Secret Garden marks my 6th musical at the Arden. I’ve had the great fortune during my time to work on a world premiere (Tulipomania); two Sondheim’s (A Little Night Music, Passion); a Pulitzer Prize winner (Next to Normal); and a musical with a Tony Award winning Best Original Score (Parade).

What keeps me interested in returning each season is 1) the material chosen is always first rate – The Secret Garden is no exception, with a Tony Award winning Book and a much loved, iconic score – and 2) the Arden’s dedication to making each musical they tackle a “new” production. “New” meaning that the production is conceived and crafted specifically for the Arden’s audience and artists to experience and tell the story in a completely unique way. As part of the creative team that works on bringing these musicals from the page to the stage, my goal as the music director is to serve the score through the new lens from which we are viewing our production.

Ryan Touhy at the first rehearsal for The Secret Garden.

Let me break it down by the numbers for some context:

In 1991, The Secret Garden opened on Broadway with a cast of 23 actors and a 24-piece orchestra. At first glance, what makes the Arden’s production “new” from a musical perspective is that we’ve reconfigured the show for a cast of 15 actors and had new orchestrations rendered for a 9 piece orchestra, with two additional orchestra members added at specific points in the score by 2 members of our cast. This is commonly viewed as a reduction of the original production. For me, when you reduce the size of a cast and orchestra, you are increasing the importance of the players you have to tell the story – each person is that much more crucial to the successful execution of the material. It also calls for some creative problem solving.

We started making decisions musically for the production over a year ago, when we began casting the show in February of 2015 (we finished casting in March of this year). The selection of each actor, for a musical that has large ensemble sequences, dramatically impacts where I utilize their voices in any given moment based on their skill set. For instance, in the opening sequence of the show, which includes large ensemble numbers such as “There’s A Girl Whom No One Sees”, “The House Upon the Hill” and “I Heard Someone Crying”, the score clearly specifies which character sang each harmony part in the original Broadway production. With the new given circumstance that I only have 15 actors available to me (less than all the characters delineated in the score) I began solving a puzzle – how could I reconfigure each section in the score with multi-voice harmonies to suit the strengths of our cast without sacrificing the musical integrity of the score?

I spent 3 months prior to our first rehearsal considering where each actor would fit to make the music have the same visceral effect as it would if 23 actors were singing. These decisions are made alone. Usually in my bedroom. Usually late at night. These early decisions are initial hunches I have about which actor would serve the score best on any given line of music. Many times those hunches prove to be true once you are in the room with the real people but there are plenty of times where they don’t work out as you may have heard them in your head. Time is then spent in the rehearsal process tweaking and refining those decisions to better serve our actors and the production (we made musical adjustments all the way up to the final afternoon rehearsal the day of our opening performance).

This timeline for how much musical consideration is given in advance of being in the room with actors and musicians may come as a surprise but I would venture to say that for every minute spent in a rehearsal room with actors or musicians making music, there’s probably 4 times as much preparation we do alone as music directors giving careful consideration to how we can best serve the score. Making music feel expressive and effortless takes a lot of time.

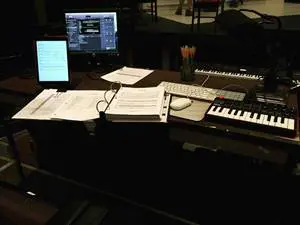

Ryan Touhy’s work desk for The Secret Garden.

The amount of consideration I gave to what makes the most musical sense for this production was coupled with giving equal consideration to what makes the most dramatic sense as well. Terry, our director, was very much interested in viewing the production through the lens of Mary Lennox. Terry, Niki (our choreographer), Amanda (our conductor) and I sat down prior to rehearsals and mapped out how our decisions musically could have resonance dramatically – what would happen if we had a character or a certain combination of characters connected to Mary’s past sing a line of text in this given moment, how could that resonate with her or with us or how could that strengthen the relationships in the story. Sometimes these choices matched what was already specified in the score, many times it was a new way into the material.

Much of my time in rehearsals, beyond the initial teaching of the score’s skeletal structure (the notes and rhythms of everything the actors sing), was dedicated to bringing clarity to the communication of the musical text (the lyric). I’m obsessive about words. Every sound counts as it can have emotional resonance for both the character and the audience. Every consonant gives us the action of the word; every vowel gives us the emotion. I started a self-funded campaign in rehearsals called “No Sound Left Behind”. I wanted every word to be heard – no exceptions.

A score for a musical is meticulously crafted and honoring what is on the page is always a high priority but there are times where you will encounter decisions that were made musically for an original production that don’t necessarily serve your group or production. An example of this is tempo (the rate of speed a piece of music is played). In a dramatic sense – tempo is the rate of speed at which a thought is voiced. We took a great deal of time discovering what was the most effective rate to voice a thought in every moment of each song. Tempo is delicate because it affects breath, both of the actor singing but also of the musician playing. The rate of speed can be good for the actor but can sabotage the orchestration in any given moment so finding the balance of both worlds is an exciting creative challenge.

We brought together a remarkable group of actors and musicians for this production. Their appetite for precision, openness to try every possible musical configuration to find the most effective choice and the joy they bring to singing and playing this music brings a fresh perspective to the score. You are hearing the score for The Secret Garden in a completely new way that won’t be heard again.

Ryan Touhy conducts a music rehearsal for The Secret Garden.