Charles Dickens in the City of Brotherly Love

On an 18 degree January night in Philadelphia in 1868 people lined up on Chestnut Street before midnight, cure bringing tents and blankets, prepared to camp out in order to be first in line. What were they waiting for? Tickets to see the novelist Charles Dickens, >drug reading selections from his novels. The first six readings were sold out in four hours and the Public Ledger declared “a state of popular excitement that, taken in all its phases, is without parallel on our side of the ocean.” When Dickens left the city for what was to be the last time, the Inquirer wrote: “the remembrance of his visit will be a life-long possession.” In fact, the remembrance of his visits would stay with the city much longer than that.

Despite explicit instructions in Dickens’ will that he be remembered by his words and not by statues, in 1893, the sculptor Frank Elwell created a life-size statue of him for the Chicago World’s Fair. Upon the closing of the Fair, the statue was sent to England to Dickens’s family, who, angry at the violation of Dickens’ wishes, returned to sender. The statue never made its way back to Chicago, ending up instead in a

a life-size statue of him for the Chicago World’s Fair. Upon the closing of the Fair, the statue was sent to England to Dickens’s family, who, angry at the violation of Dickens’ wishes, returned to sender. The statue never made its way back to Chicago, ending up instead in a

Philadelphia warehouse, where it was purchased in 1901 by Clark Park in West Philadelphia, where it remained the only statue of Dickens in the world for over 100 years, though a few have emerged in the last few years. You can still visit it at Clark Park (4398 Chester Ave).

In 1984, Strawbridges’s and Clothier commissioned artists Ray Daub and Mary Wimberly to create a Christmas display. Daub remembered his family reading A Christmas Carol every year, and so he made the Dickens Christmas Village: a miniature replica of 1843 London with animatronic figures acting out scenes from A Christmas Carol. The Village is such a draw that when Strawbridges’s closed, Macy’s rescued the village and installed it in their 13th and Walnut location on the third floor in time for Christmas. You can still see it there starting November 29th.

In 2012, Philadelphia celebrated “The Year of Dickens” to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the author’s birth. With a year of events, the celebration was one of the largest held outside of the UK. It makes sense. Following Dickens’ death, his relatives sold off many of his possessions in order to make ends meet. Many of them ended up in collections at two of Philadelphia’s most venerable institutions for bibliophiles—the Rosenbach Museum and Library and the Rare Books Department of the Free Library—have impressive Dickens collections. The Rosenbach boasts many Dickens letters, special editions of the books, rare photographs, manuscripts and a few first printings of his novels in installments. These are currently on display in the Rosenbach’s Hands-On Tour for Dickens in which patrons are able to handle some of these rare items under the guidance of a member of the Rosenbach staff (2008-2010 Delancy Street).

The Rare Books of Department at the Free Library has one of the most unusual Dickens’ holdings in the world: Grip, Dickens’s pet raven which was stuffed and mounted after his death. Grip was a minor character in Dickens’s short story, Barnaby Rudge, which Philadelphian Edgar Allen Poe reviewed in his capacity as a literary critic. While Poe enjoyed the story, he felt there was more to mine in the character of the raven. In addition to Grip, who presides imperiously over the Rare Books Department hallway, the Free Library also boasts

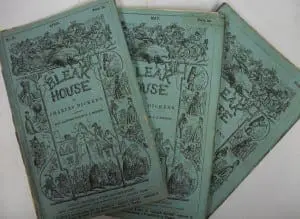

possession of a desk and chair belonging to Dickens, sets of Dickens’ work in their original parts (the original installations, see image), first additions, and original artwork, including the set of parts for The Pickwick Papers inscribed by Dickens to his sister-in-law Mary Hogarth. All of these can be seen Monday-Friday on the daily tour of the Department at 11am (1901 Vine Street).

Dickens first toured the United States in 1848 and wrote about his travels in his nonfiction book: American Notes for General Circulation. Of Philadelphia, he writes: “It is a handsome city, but distractingly regular. After walking about it for an hour or two, I felt that I would have given the world for a crooked street. The collar of my coat appeared to stiffen, and the brim of my hat to expand, beneath its quakery influence.” While he was impressed by Philadelphia’s hospitals, libraries, and post offices, he was horrified by a visit he made to Eastern State Penitentiary (2027 Fairmount Avenue) which forms the bulk of his write-up on the city: “In the outskirts, stands a great prison, called the Eastern Penitentiary: conducted on a plan peculiar to the state of Pennsylvania. The system here is rigid, strict, and hopeless solitary confinement. I believe it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong.” Dickens acknowledged the effort to be well-intentioned, but greatly objected to the amount of solitary confinement imposed on the prisoners. Despite his reservations, Dickens returned to Philadelphia a second time in 1868 in which he gave, by all accounts, an energetic, heartfelt, and exciting reading of his novels.