How to build a pool onstage (or, How I spent my summer vacation)

By Glenn Perlman, Technical Director

Over the last couple of years, during season planning discussions each spring, I’d heard rumblings about us doing Metamorphoses — or as theatre technicians commonly refer to it: the pool show. It would come up, then go away. And each time it didn’t make our season schedule, I felt like we dodged a bullet.

Then it didn’t go away.

Learning that we were to produce Metamorphoses must be a little like expectant parents learning they’re going to have twins: you knew it was going to be hard, but it just got a whole lot harder.

Fortunately, we were as prepared as possible. Courtney Riggar, our production manager, had worked on a prior production at Hartford Stage when she was there. She ran the crew and remembered all the challenges. And she knew some guys that built it and we could ask them questions.

The technicians that created the original and subsequent Lookingglass productions had created a “pool bible:” a document with many important details about the design and construction of the pool and equipment.

Our director, Doug Hara, had been in several productions, including the original and the Tony-nominated Broadway run.

But the single biggest resource we had was time. We reserved the Haas stage for the entire summer for the build. Master Carpenter Justin Romeo and I had what seemed like all the time in the world to create this tricky little set.

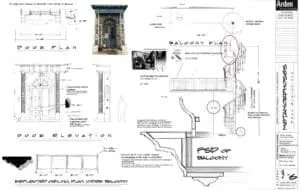

We started right after Independence Day; first moving the seats into our thrust configuration, and then we started building the pool. Working from detailed designs by set designer (and Lookingglass Theatre alum) Brian Sydney Bembridge, we began construction of the pool container itself. I had done my homework: calculating water volume (2600 gallons) and weight (around 10 tons), figuring the load per square foot on the stage floor (54 lbs/sq ft.) and engineered a construction method robust enough to contain the water. Scenery is usually pretty light weight, but this thing is beefy — 2×6 framing on 16″ centers, double top-plate and covered in 3/4″ plywood. The sidewalls are braced every four feet to prevent collapse. The entire bottom and sides are also covered in 1″ thick blue styrofoam, for heat insulation and actor comfort on their feet, and then the thick black rubber pond liner, which is in one giant seemless piece.

Installing the liner was like gift-wrapping a present, but opposite — like trying to neatly wrap the inside of a box. But the pool isn’t just a rectangular box: the top (upstage) is the shallow end: just 2″ of water. Through the middle of the stage the bottom slopes down and then downstage there’s the deep end, at 22″. The downstage corners also have 45° angles. This is no ordinary gift wrapping project. We roughed it in then started adding water to help push the liner into the corners as we worked it out smooth and flat. This was our first fill up, and it took about 7 hours running a hose from the nearest utility sink backstage.

Well it worked, and it held the water, it didn’t leak, the sidewalls didn’t collapse, and everything looked good. But you wouldn’t want to swim in it yet. The water was cold and full of floating sawdust. So the next step was pool equipment and plumbing.

Working with a pool and spa contractor I found in Lancaster (after being rejected by a few places that didn’t want anything to do with this crazy scheme of a temporary indoor hot tub) we assembled all the necessary gear and started the install.

We had drained the pool after our initial pressure-test, and went to work. Using industry-specific equipment, we spent a magical day, now early August, cutting the holes in the sides of the box for suction and return water, running all the pvc plumbing, and installing the pump, filter, two 11 kilowatt heaters, and automatic chlorinator. All of this gear lives under the deck just behind the pool. Our Master Electrician, Martin Stutzman, built the temporary power distribution for the gear, requiring two 240v 60 amp GFCI breakers for the heaters. This is serious business.

It’s actually more like a hot tub, technically. We need the water temperature to be at 104° at the beginning of the show, when the audience enters, because that’s when we shut the pump off. This lets the water settle and be still and flat; which along with the black liner underneath and use of Thom Weaver’s beautiful lighting makes the pool like a mirror. Or infinite. Or both. It’s art. But as soon as the heaters and pump go off, the water temperature starts falling. Actors spend 90 minutes in and out of the water, often in full costumes, so it needs to be warm so they don’t get sick. They need to do this 9 times a week, after all. In fact, on both sides of the stage we built small, heated, insulated dressing rooms called “hot boxes” for them to retreat to after exiting the stage. Actor safety and comfort is always primary.

As soon as a performance ends, the pool gets cleaned of floating debris from the performance, covered with an insulating pool cover, and the pump and heaters get switched back on to bring it up to temperature for the next show. Pool chemical levels are monitored daily. And every two weeks we will completely drain, clean, and refill the pool.

Oh, and there’s also an entire set around the pool as well, including the amazing sky which was painted by our incredible Charge Scenic Artist, Kristina Chadwick, using a technique involving sawdust and fine misty layers of paint sprays to create those beautiful clouds.

In all, Justin and I worked on this set for about ten weeks. And there are four weeks of performances. It has been one of my most challenging yet rewarding sets ever, and I am really proud of how it turned out. And I personally think the show is beautiful and really worthwhile, so that’s nice too.

I’ll never forget the time I spent the entire summer by the pool.