Remember the Porter: Updating Shakespeare’s Text

Many scholars agree that one of the chief purposes of the Porter’s speech in Macbeth is to give a much-needed comedic breath to a very dark story. Whether this scene is meant to decrease tension (by injecting some lightness and pausing the story) or increase tension (by the insistent knocking and delaying the discovery of Duncan’s body) is up for debate, >medicine but that it is meant to be humorous is impossible to deny. In the Arden’s production of Macbeth, we wanted to honor this intention, which, for us, meant updating some of the language.

As Bruce Graham, playwright of our upcoming production of Funnyman has said—nothing goes stale faster than comedy. Even Shakespeare is not immune. Much of the Bard’s work is universally comedic—gross-out jokes always kill. But some of his comedy is specific to the time and place for which it was written, and many of the topical references fall flat for contemporary audiences. One of the best examples of this is the Porter’s reference to equivocators: “here’s an equivocator that could swear in both the scales against either scale.” Shakespeare here alludes to the infamous trial of Henry Garnet, recently hung as a traitor. While Shakespeare experts might know that this trial was likely on the minds of the Jacobean public, for most contemporary audiences, the word is unfamiliar and the reference impenetrable. Thus humor is lost.

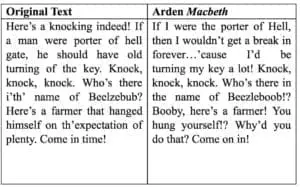

When director Alex Burns and Chris Mullen, who plays the Porter, started working on this scene, they began with the text. After a few times through, Chris asked if he could try to change the text a little bit to make it more his own, and Alex enthusiastically agreed. They wanted to honor the spirit of the Porter scene while ensuring that the jokes weren’t obscured by the language or the distance between our world and Shakespeare’s. Together, Alex and Chris played around with language, letting Chris improvise using contemporary equivalents for some of the characters the Porter mentions. He went very far in some cases—at one point, a stock-broker awaited admittance to hell. Shakespeare’s equivocator became a lawyer, because, in the words of Chris Mullen “lawyers are always funny.” After a few rounds of improvisation, Alex and Chris set the text, using the cast as a test audience to see what was funny and what fell flat (see below for an example). They continued to refine over previews before landing upon what you saw in the performance. In the end, the essential beats of the Porter’s speech remain, as does the subject matter, and even some of the words.

Often in Shakespeare’s day, characters like the Porter were the specialty of clowns, who were allowed freedom to play with the audience—to go off script and improvise. Here was the audience’s much relished chance to interact directly with the performers. How much those performers talked back is still debated. Many scholars believe the role of the Porter to have originated with Robert Armin, the prolific clown of Shakespeare’s company, who was known for his intelligent humor, and is often credited with the complex philosopher-fool characters of some of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, including the Fool in King Lear and Feste in Twelfth Night. Armin’s portrayal of the Porter—filled with topical references and perhaps even imitations of public figures—would have had audiences rolling in the aisles. He had the advantage of speaking the same language as his audience. We wanted to give Chris and our audiences the same opportunity by honoring the spirit of Shakespeare’s text and his favorite clown.