Black Market Relics

Though the black market in relics depicted in Incorruptible was perhaps exaggerated in scale to serve the story, playwright Michael Hollinger drew upon inspiration from historical record. Relics, the physical remains of a holy person, were prized in the Middle Ages for their ability to grant miracles. Some relics were passed down through generations, while others changed hands many times. With the demand for relics came opportunists, capable of supplying a relic even when none were to be had.

In an age characterized by war, disease, and draught, one of the few certainties of the Middle Ages was the power relics had to ward off destruction. Caught a mystery illness? Pray to the relic for relief. Late frost endangering the crops? Pray to the relic for a better harvest. A relic was defined by the miracles it created. In fact, even a fake relic could become a real one if it achieved a miracle.

The need for relics was not solely spiritual. Pilgrims would travel great distances to visit a holy relic. A type of tourism, with the influx of pilgrims into a community would come an influx of money. The presence of a miracle-granting relic could prop up the economy of an abbey or a village.

Rarely was a relic sold or given away. So if one was in need of a relic there were two options—buy or steal. Given the finite number of saints and body parts, and the large population in need of miracles, medieval opportunists were quick to see profit potential. In fact, so high was the demand for relics and so rampant were counterfeits in the Middle Ages, that the leadership of the Catholic Church started to issue authentication tags for saints, although the tags were, as it turned out, very easy to forge. A church in Geneva proudly displayed the brain of St. Peter, until one day the brain was moved and was discovered to be a pumice stone. Since forensic science was somewhat lacking in the Middle Ages, if the relic was a real bone, authentication became trickier. The only real way to identify a fake was if someone else claimed to have the same relic, which happened fairly often. The question over which of St. Foy’s remains are the real ones in Incorruptible would not have been unusual. In his classic treatise on the dangers of revering relics, John Calvin, the Protestant reformer, claimed that if all the relics spread out over Europe and beyond were brought together “it would be made manifest that every Apostle has more than four bodies, and every Saint two or three.” The only way to know a “real” relic was by determining whether it had performed any miracles.

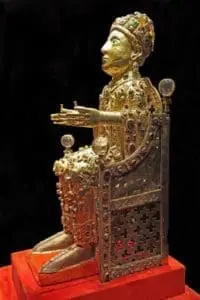

Stealing relics was a frequent recourse for those wary of buying fakes. While Hollinger’s rendering of the theft is fictionalized, St. Foy, the saint in question in Incorruptible, was part of a high-profile Dark Ages crime. St. Foy was housed at the monastery of Agen. Lacking any relics of their own, the Abbey of Conques sent one of their monks to infiltrate Agen. According to one legend, the monk ingratiated himself at Agen for over ten years before finally making his move and absconding with the saint back to Conques. Conques quickly began to prosper, attracting enough pilgrims that they soon required a larger church. The monks were quick to point to this sudden windfall as a miracle, proving that St. Foy was happy in her new home.